Traditional Villages

The Indians of the Puget Sound lived in permanent villages along the shore near rivers and streams, with rectangular houses facing the water. These villages consisted of large wooden houses, called longhouses or winter houses, which were often shared by many families. The houses were made of cedar planks and logs, and had shed or gabled roofs. They varied in size with some of the larger structures ranging from two hundred to six hundred feet long. They were divided into individual rooms, which opened to the outside.

The Suquamish had winter villages at Suquamish, Point Bolin, Poulsbo, Silverdale, Chico, Colby, Olalla, Point White, Lynwood Center, Eagle Harbor, Port Madison and Battle Point. The best known winter village was Old Man House , the home of Chief Seattle and Chief Kitsap.

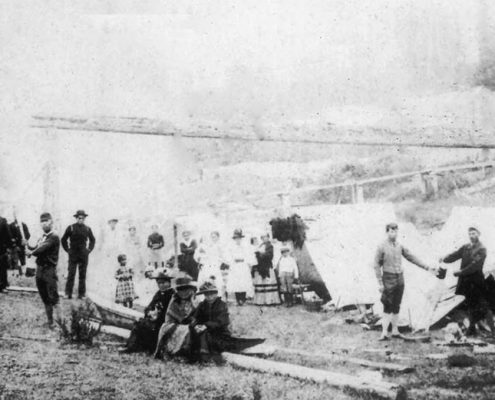

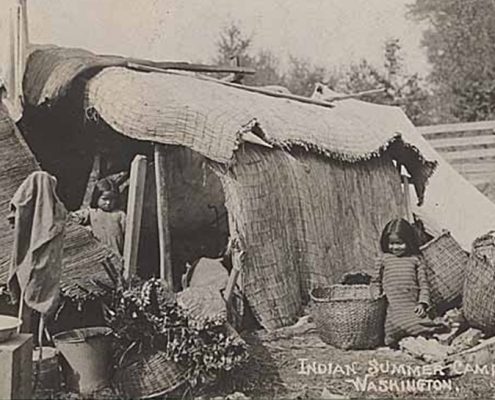

Traditionally, Suquamish periodically left their winter residences in the spring, summer and early fall in family canoes to travel to temporary camps at fishing, hunting and gathering grounds. The seasonal camps consisted of portable frames made of tree saplings covered with woven cattail mats.

Today, the Suquamish continue to work cooperatively to provide housing for Tribal Members on the Port Madison Indian Reservation with the creation of a comprehensive Tribal Housing program.

Historical Village Locations

Language

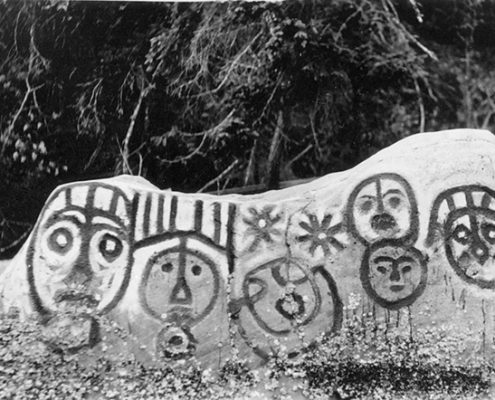

The traditional language of the Suquamish People is Lushootseed, a member of the Coast Salish language group spoken by first peoples from throughout the Northwest including the areas surrounding the Puget Sound in Washington State and the Strait of Georgia in British Columbia.

“When I was small, I heard very little English. About the only time you heard any English spoken was when old Bartow, the Subagent, would come and give a speech or ask questions. The Indians would give him his answers in English, but as soon as he left everybody was talking Indian again.” – Lawrence Webster, Suquamish 1899-1991

Failed Federal assimilation policies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries resulted in the near loss of the language. However, a dedicated group of Suquamish have been diligently working to revive the language. Today, the Suquamish have a Traditional Language Program that teaches Lushootseed to both school children and community members.

Fishing, Gathering & Hunting

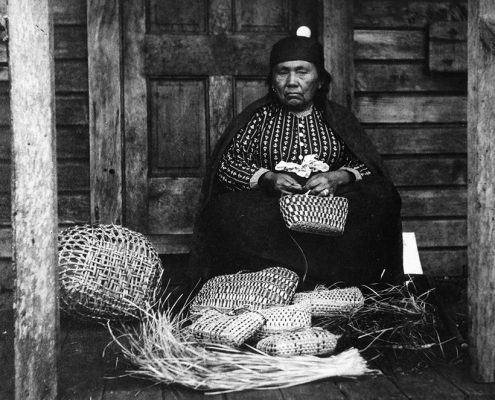

The Suquamish depended on salmon, cod and other bottom fish, clams and other shellfish, berries, roots, ducks and other waterfowl, deer, elk and other land game for food for family and community use, ceremonial feasts, and for trade. Traditionally, fishing was the most important source of food for the Indians of the Puget Sound. Today fishing remains an important livelihood for many tribes. The Suquamish fished widely throughout Puget Sound, and continue to do so today. The absence of a major river with large runs of salmon required the Suquamish tor travel widely on the marine waters of the Salish Sea to catch their supply of salmon. A great deal of skill and knowledge was and is needed to determine when and where various kinds of fish can be caught. The state of the tide, concentrations of birds and seals, the level of water in streams, the weather and other more subtle signs in the environment when planning their harvests. Historically, success in trade and sophisticated food preservation techniques permitted Puget Sound Indians to devote winter months to social gatherings and other activities.

The Suquamish produced a variety of ingenious tools and other devices to efficiently harvest fish and gather other foods. The Suquamish caught salmon with nets, traps, weirs, hook and line, and netting from canoes. Chinook, Coho and Chum were the salmon most frequently caught in local water. In addition, several kinds of trout were caught by these methods; while other fish were caught with lures or speared. Lines and nets were often made from nettle stems and roots.

Canoes

The dugout canoe was an integral part of Suquamish culture. This craft was the major form of transportation. The heavily forested land made efficient foot travel difficult. The canoe was essential to the collection of subsistence resources such as salmon and other fish, berries, roots, wild potatoes and sea grasses. These foods were seasonal and regional, and the Suquamish needed to be in particular places at specific times of the year in order to harvest them. The canoe allowed them to travel long distances in a relatively short time, assuring quantities of food, establishment and renewal of tribal alliances and the preservation of social and ceremonial contacts, which in turn permitted the culture to flourish beyond mere survival.

A good canoe, made in the traditional manner usually took one year to complete. The canoe maker was trained in the art from an early age, usually with much practice in producing models and small one-person craft. Most men were capable of making a simple canoe, but only the masters were able to make the larger versions successfully. The first step was to select the proper tree. It had to be straight and tall, have few branches, be near the water, free of rot and have a soft place to fall. Western Red Cedar and Yellow Cedar were to two suitable species: both are lightweight, hard, and preserve well due to their oiliness. The tree was felled by either carving a notch at the base and burning the wood the rest of the way through, or by chiseling the base completely through. Next the log was roughly shaped enough to allow transport to the beach near the village where detailed work took place. This was done with chisels and wedges struck with hand mauls. The canoe was turned upside down and the hull was carved to perfection then turned over and hollowed out. Then it was filled halfway with water and hot stones in order to create steam to spread the sides. Cross sticks were used to keep them spread. Some tribes attached separate bow and stern pieces with cedar pegs, completing the fine line and adding character to the finished canoe.