Indian Child Welfare Act is needed to protect Native American children from a return to the Dark Ages

Native American children need family, tribe, not forced separation

By Leonard Forsman, published in the Seattle Times Opinion Section, Nov. 25, 2022.

A case argued in front of the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month threatens to revive a dark period in our history when Native American children were taken away from our families and tribes.

Until 1978, when the Indian Child Welfare Act was signed into law, non-Native officials decided when to remove our children and where to place them. If our families were poor or didn’t have running water, parents could be labeled as inadequate, and our children could be removed from their families. In all, nearly a third of American Indian and Alaska Natives were being taken from their homes, with 85% placed in non-Native homes. Their families and tribes might never see them again.

The problem was so egregious and widespread it took congressional passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) to change these practices. The 1978 law created a common-sense framework that protects our children and protects our rights to raise our next generations. This law could be declared unconstitutional by an activist Supreme Court.

ICWA assures that a Native American child’s extended families and other qualified members of their tribe have an opportunity to care for a child whose parents are not able to raise them. If the child is placed with non-Natives, ICWA assures that their tribe can keep them connected to their community and culture, and can check in on their well-being. And this means that their rights as citizens of sovereign Indian nations are also protected.

To implement these policies, tribes have developed child welfare agencies that have been effective and compassionate at overseeing the best interest of the children, winning a “gold star” rating from 31 non-Native child welfare organizations.

All this progress could be reversed as a result of a case first brought in 2017 to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas in Brackeen v. Zinke. This case was consolidated and renamed Brackeen v. Haaland as it made its way through the courts, and is currently being heard at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Those challenging the law say it is race-based discrimination. It is not. The Indian Child Welfare Act is founded in our sovereignty as nations with spiritual and cultural connections that precede the founding of the United States by thousands of years, confirmed by treaties, legal precedents, Congressional action and federal recognition. We have the right to make laws and enforce them, to govern ourselves and to see to the welfare of our families and children.

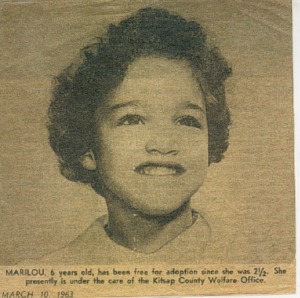

In my tribe, we know only too well what it means when we don’t have the protection of the Indian Child Welfare Act. On the wall of the Suquamish Museum is a photo of a young girl, taken from an old newspaper clipping. The caption reads, “Marilou, 6 years old, has been free for adoption since she was 2 and a half.” This is a photo of Mary Lou Salter, now a tribal elder, who was taken from her home, her extended family and her tribe when she was just 18 months old. For decades, her extended family and her tribe had no way to reach her or to see if she was all right.

Mary Lou Salter, now a Suquamish Tribal Elder, as a child in the state welfare system.

“I had no idea there were relatives who worried about me — who remembered me,” Salter said.

It turned out she wasn’t all right. Over the course of many years, she was shuffled from foster home to foster home, and many of these homes were abusive. She went deaf as a result of chronic, untreated ear infections, which eventually required surgery and caused deep pain. She was eventually adopted against her will.

It wasn’t until she was nearly 30 years old that she found her way back to her family and tribe, and it was only then that she learned how much her family and community had missed her.

“It would have made a huge difference to have remained in the community and to know my relatives and to have a sense of belonging somewhere,” she said. “When I first came back, the elders would crowd around me and touch me, not saying anything. One of them told me that they were trying to pass their memories to me.”

Mary Lou’s story is like thousands of others of Native American children removed from families and communities, and the abuse and trauma that so often followed.

Opponents of the Indian Child Welfare Act say its protections are no longer needed, and that Native children should be treated like any other children.

But they fail to see the traumatic history that has broken up so many Native families, including the history of forced taking of Indian children to boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their language, and many were subjected to physical, physiological and sexual abuse. This history, which played out in parallel ways in Canada, was declared genocidal in the 2015 report of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. And a U.S. Department of Interior report released in May 2022 concluded: “The Federal Indian boarding school policy was intentionally targeted at American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children to assimilate them and, consequently, take their territories.”

Restoring our families is among our highest priorities. Even with ICWA, Native children are removed from their homes at four times the rate of non-Natives — even when the family situation is the same.

Opponents like to focus on the successful placement stories, when Native children land in supportive non-Native homes. But they fail to acknowledge the many foster homes that are abusive, or that deny or demean the children’s Native heritage. When the tribes and extended families can’t contact these children, they are unable to check on their safety and well-being, and to connect them to their culture.

Opponents often speak of the attachment the children form to their foster parents. But they don’t see the deep attachment that exists with the extended family and the tribal community. Nor do they talk about the way our children are often deeply traumatized by being separated from their extended families, tribes, their culture and their identity.

They don’t mention the robust child welfare agencies tribes have developed to assure the well-being of children.

And they fail to see that these children are our citizens and future leaders. They fail to recognize our sovereignty and the fundamental right we have to care for and raise our next generation.

“We’re not asking for special treatment,” Mary Lou Salter said. “We’re asking as a sovereign nation that we be allowed to look after our kids and keep our families intact.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act is needed to protect Native American children from a return to the Dark Ages of shattered families and traumatized children.