Suquamish Tribe Opposes North Kitsap Schools Bond Measure

The Suquamish Tribal Council decided at their Jan. 22, 2024, meeting not to endorse the North Kitsap School District 2024 Capital Bond Measure.

The Tribe has a track record of supporting public education in North Kitsap. Our commitment has taken the form of earlier endorsements of school levies and bonds, as well as frequent gifts from the Suquamish Foundation to individual North Kitsap teachers, schools, programs, and athletic activities.

However, excluding the Suquamish Elementary School from the bond measure is not equitable for children in our community, nor for the hardworking school staff who educate our students.

We are confident the district can return to voters at another time with a bond measure that we can support and that will more equitably and effectively meet the needs of all the district’s students and staff.

PRESS ADVISORY — Canoe Journey 2023: Suquamish Tribe Hosts Last Stop Before Muckleshoot’s Alki Beach Landing

SUQUAMISH, July 2023 — Tribal Canoe Journey is back for the first time since COVID, and the Suquamish Tribe is hosting the last stop before the final landing at Alki Beach. An estimated 100 canoes from throughout the Northwest and Canada will be arriving on the beach in front of the House of Awakened Culture in Suquamish on July 28, 2023. About 9,000 people will spend two nights here before they make the final paddle on July 30 to Alki Beach and the Muckleshoot Tribe’s hosting.

Reporters, photographers, and filmmakers are invited to attend and report on this event. In order to prioritize the integrity of the ceremony and the safety of canoe families and hosts, media representatives are asked to follow the Tribe’s ground rules and obtain a press pass by filling out this form: https://suquamish.nsn.us/for-media-how-to-participate-in-the-tribal-canoe-journey-stop-in-suquamish/

Highlights of the Suquamish hosting include:

Friday, July 28, 2023

Noon to 4pm: Canoes arrive and request permission to come ashore to rest, share stories, and share traditional foods. Suquamish hosts welcome them, and canoes are carried up the boat ramp to the lawn in front of the House of Awakened Culture, the Suquamish Tribe’s longhouse and community gathering space.

5pm: Seafood dinner is served to 9,000-plus people traveling on the water or supporting the canoe families.

7pm: Protocol begins during which visiting canoe families share songs, dances, stories from their travels, and gifts inside the House of Awakened Culture. The tribes that travelled the longest distances are the first on the floor.

Saturday, July 29, 2023

Noon: Protocol continues, dinner is served at 5pm, and protocol resumes at 6pm.

Sunday, July 30, 2023

Morning: Canoe families are released for the final stage of the journey to Alki Beach. Canoes are packed down the boat ramp by paddlers and volunteers. Suquamish canoes, which joined other canoe families in Bellingham, on Lummi land, continue with all the other canoes paddling the last leg of the 2023 journey to Alki Beach, where the Muckleshoot Tribe will welcome the paddlers.

Resources:

The Suquamish Tribe will make photos, press releases, and drone footage available to the media. Contact us at the link below, or include a request in the press form linked to above.

###

Contacts:

Communications@Suquamish.nsn.us

Sarah van Gelder

Suquamish Tribe Communications Manager

Cell: (206) 491-0196

Jon Anderson

Suquamish Tribe Communications Coordinator

Cell: (206) 999-3912

A statement from Suquamish Tribal Council on Brackeen v Haaland Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court decision upholding the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) is an affirmation of Tribal sovereignty and the rights of Indian nations to raise our children and the next generation of citizens and leaders.

The Indian Child Welfare Act protects our children, families, and communities from earlier government-sanctioned practices of family separation. Forced attendance at boarding schools – along with child welfare practices that removed children from parents, extended families, and tribal communities – have traumatized our people. This was a deliberate federal policy of assimilation designed to eradicate our culture and dispossess our land.

With today’s ruling, the majority of Supreme Court justices stand with us – along with child welfare advocates and legal experts – in understanding that we as tribal communities have the right to raise our children. The Supreme Court also reminded the states of the unique legal and political relationship between Indian Tribes and the United States Congress.

The Supreme Court’s ruling on Thursday, June 15, in Brackeen v Haaland should put to rest questions about the future of ICWA legal protections for our families.

Suquamish Tribe’s 2022 charitable giving approaches $1 million

Most help goes to Kitsap County organizations

Lawrence Devlin, a veteran with KC Help, refurbishes electric wheelchairs, hospital beds, and other medical equipment in his garage and donates them to local residents in need. Elsewhere in Kitsap County, a small group of moms works to make sure new mothers get support during the critical first months of their babies’ lives. When teachers need extra help to enrich their students’ learning, the North Kitsap Schools Foundation is there to help with small grants.

These are just three among dozens of local groups who have received support from the Suquamish Tribe. Much of this giving happens via the Tribe’s charitable nonprofit, the Suquamish Foundation. In the third quarter of 2022 alone, the Suquamish Foundation donated $150,437 to charitable organizations, schools, Native American groups, event sponsorships, and civic organizations, mostly in Kitsap County. The Suquamish Foundation’s total giving for the year was $530,876.

The Tribe’s business ventures, which operate under the Port Madison Enterprises (PME) umbrella, also contribute generously. PME donated an additional $222,164 to local groups, in 2022.

Suquamish Tribal government donated another $210,000 to area first responders.

Total funding from the Tribe’s foundation, enterprises, and government totaled more than $960,000 in 2022.

The Suquamish Foundation: The Tribe’s nonprofit arm

The Suquamish Tribe’s Foundation is a tribally chartered non-profit that contributes each quarter to groups that support the quality of life, environment, and culture of the central Puget Sound region.

Some of the Foundation’s largest ongoing gifts go to Kitsap Strong.

“The Tribe offers essential core funding we rely on to do the long-term innovative work of forming healthy relationships within ourselves and with others,” says Cristina Roark, Kitsap Strong Director, Community Innovation. “With the Suquamish Tribe’s ongoing support, Kitsap Strong is able to help all people in the Kitsap community heal from intergenerational trauma and toxic stress. This work — based on the latest research around protective factors and the Indigenous wisdom of our ancestors — helps build individual hope and community resilience.”

The Tribe also contributes matching funds to Kitsap Great Give, as it has since the first year of the group’s countywide funding campaign.

These matching grants are designed to support community contributions that strengthen Kitsap County by encouraging a spirit of reciprocity, says Suquamish Foundation Director Robin L.W. Sigo.

“The Tribe encourages people to give local,” Sigo said. “We want to see funding go where area residents want the support to go.”

Addressing pandemic impacts on area nonprofits

Requests for support received by the Suquamish Foundation this year reveal some of the lasting impacts of the pandemic, according to Sigo. Many area nonprofits, civic groups, and schools were unable to hold the fundraising events they relied on for support prior to COVID, so some were scrambling to make up for the lost revenue.

Meanwhile, low-wage workers, and those struggling with high housing, food, and energy bills were hit hard by the pandemic. And many already vulnerable before COVID faced even greater challenges with mental health and substance abuse.

“The Suquamish Tribe worked hard to do our part to help fill the gaps,” Sigo said. “Many of the groups we fund are small, but they make a big difference to the people they support.”

Suquamish Tribe giving extended beyond Kitsap County, including areas that are part of the Tribe’s traditional territory in Seattle and beyond. For example, one donation went to the SeaTac USO, which offers military service members and their families a place for rest and refreshment when traveling.

The Foundation also help fund the Seattle Aquarium’s planned new Ocean Pavilion.

“Their vision aligns with ours in terms of protecting the Salish Sea and the ocean as a whole,” said Sigo. The pavilion is designed to offer an experience of ocean life to visitors while supporting efforts to conserve the marine environment.

The Foundation also contributed to Western Washington University’s planned longhouse, which will offer a space for indigenous students and others to learn about the state’s tribal nations and diverse cultures.

“Western Washington University is located on Indian traditional land, but there was no place for indigenous students to gather,” Sigo noted. Like the wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ (the Intellectual House) on the University of Washington campus, the Western Washington longhouse will reflect Coast Salish design, and will support Native students by providing gatherings spaces and promoting cultural understanding.

PME helps enhance community quality of life

In addition to the Suquamish Foundation, the Tribe’s business arm is also a regular contributor to local organizations and charities.

In 2022, the Port Madison Enterprises supported Visit Kitsap, the Mike Tice Foundation, the Rise Up Academy, the Silverdale Rotary, Kitsap Great Give, the Kitsap County Fair, and Kids in Concert, among others. In all, PME gifts and sponsorships totaled $222,164 so far this year.

“As one of the largest employers in Kitsap County, our contributions are aimed at enhancing the quality of life in this community for our employees, customers, and future generations who will come after us,” said Rion Ramierez, CEO of Port Madison Enterprises.

PME includes the Clearwater Casino Resort, the White Horse Golf Club, Kiana Lodge, PME Retail (including gas stations), PME Construction, and the Suquamish Evergreen Corporation, which includes Agate Dreams and Tokem Cannabis. The PME board is appointed by the Suquamish Tribal Council.

Funding Regional First Responders

Separately, the Suquamish Tribe also made $210,000 in direct payments to area first responders in 2022. The Bainbridge and Poulsbo police and fire departments received funding along with the Kitsap County sheriff, North Kitsap Fire and Rescue, the Washington State Patrol, and the Suquamish Police. A multi-jurisdictional training program for police and fire districts also received support. The payments take place in alternate years as part of the Tribe’s gaming compact with the state of Washington.

Suquamish Tribe applauds new White House plans to bolster collaboration with Tribes

New initiatives expand consultation and support for critical needs in Indian Country

Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman hailed several new initiatives announced at the 2022 White House Tribal Nations Summit this week where he and other tribal leaders gathered with President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and numerous agency heads.

“The President’s statement on protection of tribal sovereignty and treaty rights was a highlight of this year’s summit,” said Forsman, who is also the President of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians. “The President spoke of respect for tribes as nations and treaties as law. He made this a cornerstone of his Indian Policy.”

Among the new initiatives are several aimed at strengthening tribal participation in management of federal lands and waters. Among them:

- The U.S. Commerce Department will join efforts with the U.S. Agriculture and Interior departments to co-steward lands and waters that have cultural and natural resource importance to tribal communities.

- The Interior Department will bolster consultation with federally recognized tribes to assure government-to-government discussions take place before decisions are made, aiming towards consensus agreements. Decision makers are required to invite tribes to engage in consultations and keep records of discussions.

- A new presidential memorandum requires all relevant federal agencies to get annual training on the tribal consultation process.

Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman (top row, middle right) was among the tribal leaders attending the 2022 White House Tribal Nations Summit.

“Consultation has to be a two-way, nation-to-nation exchange of information,” said Biden in his address to tribal leaders gathered for the summit. “Federal agencies should strive to reach consensus among the tribes.”

Tribal nations, added Biden, “should know how their contributions influenced the decision-making.”

Supporting protection of lands and waters

Forsman applauded the administration’s commitment to working with tribal nations.

“The administration’s stance gives the Suquamish and other Northwest tribes more leverage in our continuing efforts to protect our waters and lands from pollution and harmful development,” said Forsman. “This policy also bolsters our fight against unconstitutional attacks on our sovereignty in the courts as seen in the Brackeen and Castro-Huerta cases, both of which were recently taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Also at the summit, the Biden administration announced a new agreement on access to electromagnetic spectrum for tribal nations, as well as deployment of broadband and other wireless services on tribal lands.

The administration promised assistance to tribes for transitioning to clean energy, including federal government purchases of carbon-free energy generated by tribal producers. Agency heads also committed to including tribal nations in the administration’s electric vehicle initiative.

Critical funding for health care, climate impacts

The administration also promised $9.1 billion for Indian Health Services. Health care services are required in tribal treaties with the U.S. government. The funding will be “mandatory” instead of varying depending on budget years, insulating tribal health services from the uncertainties that hinder consistent health care services to Tribal communities.

Meanwhile, the administration promised to help tribes survive the impacts of a changing climate. $135 million will help 11 tribal communities relocate in the wake of rising waters associated with melting glaciers and ice caps. Funds will come from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, as well as from FEMA and the Denali Commission.

“As part of the federal government’s treaty and trust responsibility to protect tribal sovereignty and revitalize tribal communities, we must safeguard Indian Country from the intensifying and unique impacts of climate change,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), who joined tribal leaders at the summit.

“On a personal note,” said Forsman, “it brought me great joy and pride to see the numerous high-level, American Indian federal appointees – including Secretary Deb Haaland – who understand Indian Country. The cultural presentations woven into the summit reminded us all of our responsibilities to preserve our native languages and culture.”

Indian Child Welfare Act is needed to protect Native American children from a return to the Dark Ages

Native American children need family, tribe, not forced separation

By Leonard Forsman, published in the Seattle Times Opinion Section, Nov. 25, 2022.

A case argued in front of the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month threatens to revive a dark period in our history when Native American children were taken away from our families and tribes.

Until 1978, when the Indian Child Welfare Act was signed into law, non-Native officials decided when to remove our children and where to place them. If our families were poor or didn’t have running water, parents could be labeled as inadequate, and our children could be removed from their families. In all, nearly a third of American Indian and Alaska Natives were being taken from their homes, with 85% placed in non-Native homes. Their families and tribes might never see them again.

The problem was so egregious and widespread it took congressional passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) to change these practices. The 1978 law created a common-sense framework that protects our children and protects our rights to raise our next generations. This law could be declared unconstitutional by an activist Supreme Court.

ICWA assures that a Native American child’s extended families and other qualified members of their tribe have an opportunity to care for a child whose parents are not able to raise them. If the child is placed with non-Natives, ICWA assures that their tribe can keep them connected to their community and culture, and can check in on their well-being. And this means that their rights as citizens of sovereign Indian nations are also protected.

To implement these policies, tribes have developed child welfare agencies that have been effective and compassionate at overseeing the best interest of the children, winning a “gold star” rating from 31 non-Native child welfare organizations.

All this progress could be reversed as a result of a case first brought in 2017 to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas in Brackeen v. Zinke. This case was consolidated and renamed Brackeen v. Haaland as it made its way through the courts, and is currently being heard at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Those challenging the law say it is race-based discrimination. It is not. The Indian Child Welfare Act is founded in our sovereignty as nations with spiritual and cultural connections that precede the founding of the United States by thousands of years, confirmed by treaties, legal precedents, Congressional action and federal recognition. We have the right to make laws and enforce them, to govern ourselves and to see to the welfare of our families and children.

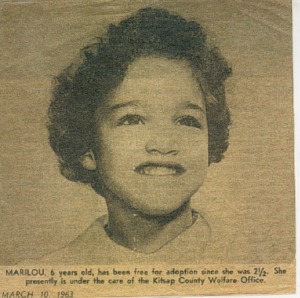

In my tribe, we know only too well what it means when we don’t have the protection of the Indian Child Welfare Act. On the wall of the Suquamish Museum is a photo of a young girl, taken from an old newspaper clipping. The caption reads, “Marilou, 6 years old, has been free for adoption since she was 2 and a half.” This is a photo of Mary Lou Salter, now a tribal elder, who was taken from her home, her extended family and her tribe when she was just 18 months old. For decades, her extended family and her tribe had no way to reach her or to see if she was all right.

“I had no idea there were relatives who worried about me — who remembered me,” Salter said.

It turned out she wasn’t all right. Over the course of many years, she was shuffled from foster home to foster home, and many of these homes were abusive. She went deaf as a result of chronic, untreated ear infections, which eventually required surgery and caused deep pain. She was eventually adopted against her will.

It wasn’t until she was nearly 30 years old that she found her way back to her family and tribe, and it was only then that she learned how much her family and community had missed her.

“It would have made a huge difference to have remained in the community and to know my relatives and to have a sense of belonging somewhere,” she said. “When I first came back, the elders would crowd around me and touch me, not saying anything. One of them told me that they were trying to pass their memories to me.”

Mary Lou’s story is like thousands of others of Native American children removed from families and communities, and the abuse and trauma that so often followed.

Opponents of the Indian Child Welfare Act say its protections are no longer needed, and that Native children should be treated like any other children.

But they fail to see the traumatic history that has broken up so many Native families, including the history of forced taking of Indian children to boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their language, and many were subjected to physical, physiological and sexual abuse. This history, which played out in parallel ways in Canada, was declared genocidal in the 2015 report of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. And a U.S. Department of Interior report released in May 2022 concluded: “The Federal Indian boarding school policy was intentionally targeted at American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children to assimilate them and, consequently, take their territories.”

Restoring our families is among our highest priorities. Even with ICWA, Native children are removed from their homes at four times the rate of non-Natives — even when the family situation is the same.

Opponents like to focus on the successful placement stories, when Native children land in supportive non-Native homes. But they fail to acknowledge the many foster homes that are abusive, or that deny or demean the children’s Native heritage. When the tribes and extended families can’t contact these children, they are unable to check on their safety and well-being, and to connect them to their culture.

Opponents often speak of the attachment the children form to their foster parents. But they don’t see the deep attachment that exists with the extended family and the tribal community. Nor do they talk about the way our children are often deeply traumatized by being separated from their extended families, tribes, their culture and their identity.

They don’t mention the robust child welfare agencies tribes have developed to assure the well-being of children.

And they fail to see that these children are our citizens and future leaders. They fail to recognize our sovereignty and the fundamental right we have to care for and raise our next generation.

“We’re not asking for special treatment,” Mary Lou Salter said. “We’re asking as a sovereign nation that we be allowed to look after our kids and keep our families intact.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act is needed to protect Native American children from a return to the Dark Ages of shattered families and traumatized children.

Tribe applauds plans to end finfish aquaculture

Suquamish Tribe applauds Washington Department of Natural Resources plans to end finfish aquaculture

Today, Washington State Commissioner for Public Lands, Hilary Franz announced new agency rules, policies, and procedures to prohibit any future finfish farms in Washington marine waters south of the Canadian border. The move follows an announcement, early this week by Franz that DNR would end leases for the two remaining finfish aquaculture facilities in Puget Sound.

The new policy and the Commissioner’s move to end aquatic leases at Hope Island in Skagit Bay and Rich Passage near Bainbridge Island signal the end of fish farming in Puget Sound by Cooke Aquaculture, five years after the catastrophic collapse of Cooke’s fish farm at Cypress Island and the release of 250,000 non-native Atlantic Salmon into Salish Sea waters. Cooke Aquaculture was fined $332,000 following the incident and cited for inadequate maintenance and poor monitoring of conditions.

Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman speaks at a press conference on Bainbridge Island applauding new plans to end finfish aquaculture in Washington state. (Photo by Sarah van Gelder)

“On behalf of the Suquamish people, I want to thank Commissioner Franz for listening to Tribes and others who place the health of the Salish Sea as their top priority.” said Leonard Forsman, Chairman of the Suquamish Tribe. “Ending commercial finfish farming in our ancestral waters is an important step towards protecting marine water quality, salmon populations, and the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales. The impacts of commercial finfish farming put all of that at risk, and threatened treaty rights and ultimately our way of life and culture.”

Before and especially since the Cypress Island disaster, the Suquamish Tribe has consistently advocated for the end of all commercial finfish farming in Puget Sound, whether for native or non-native finfish. In 2018, the Washington State legislature banned the commercial farming of non-native fish, prompting Cooke Aquaculture to seek and receive permits from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Washington State Department of Ecology to switch to the farming of native steelhead at its Hope Island and Rich Passage facilities. The Suquamish Tribe opposed those permits and has since communicated it strong opposition to all commercial finfish operations in Puget Sound to state leaders, including Commissioner Franz.

“This is a big victory for everyone who values the Puget Sound ecosystem,” Forsman said. “This action eliminates a harmful impact in our ancestral waters. The Rich Passage net pens have long been a threat to our salmon fisheries, both through their threats to our genetic stocks, the pollution associated with their care and feeding, and the physical obstruction to our treaty fishers. They have blocked and polluted our fishing grounds for too long, and we are relieved to know they will be removed, restoring our waters back to a more natural state.”

Commercial fish farming operations pose numerous environmental risks to the marine waters of Puget Sound. Because their operations are year-round, commercial finfish farming results in the constant release of chemicals, medicines, food and fish waste into the marine environment, resulting in impacts to the seafloor, water quality, and habitat. Releases like the one at Cypress Island, also put at risk the health and genetics of local, native finfish. The move towards commercial finish farming of steelhead posed an especially dangerous risk to the small native steelhead population on the Kitsap Peninsula.

Year-around net pen farming operations also attract species, such as seals and sea lions, in numbers that likely increase predation on local salmon populations as they migrate to and from spawning and rearing habitat in local streams.

Forsman urges action on Indian Boarding Schools Commission

Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman called on Congress to establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding Schools in an op-ed published today in the Seattle Times.

The call for action comes on Orange T-Shirt Day or — more formally — Day of Remembrance for Indian Boarding Schools.

“We need to learn more, including the number of children forced to attend the schools, the number who were abused, died or went missing,” writes Forsman. “And we need to know the long-term impacts on the children and the families of children who were forced to attend the Indian Boarding Schools. The Truth and Healing Commission can help with this much-needed investigation.”

Forsman also said more work is needed in identifying the best ways to address the trauma inflicted on Native communities during the boarding school era.

“Many of the students adapted, endured and found ways to overcome and succeed within the system, and became mentors and leaders of their tribal nations despite the intent of the boarding school system. Still, many suffered in the past and many former students and their offspring continue to struggle today,” writes Forsman. “Anger and resentment are justified, but we must commit ourselves to the healing process.”

You can read Forsman’s full column here.

King County Unanimously Approves Settlement with Suquamish Tribe over Sewage Spill Dispute

‘The People of the Clear Salt Water’ say Puget Sound community deserves better

The King County Council voted unanimously Sept. 27 in favor of a landmark settlement with the Suquamish Tribe to redress the repeated release of sewage into Puget Sound from the County’s wastewater collection and treatment system.

“The Suquamish Tribe is pleased that King County recognizes the seriousness of this issue and worked with us to protect Puget Sound,” said Suquamish Tribal Chairman Leonard Forsman.

The settlement is designed to curtail further wastewater pollution of Puget Sound from King County facilities, including the West Point Wastewater Treatment Plant (WPTP). The settlement also funds ecological restoration projects in Puget Sound that will support the recovery of salmon, orca, and other marine life, and it compensates the Tribe for past releases that continue to impact Tribal fisheries.

Settlement talks began following a July 2020 notice from the Suquamish Tribe that it intended to file a lawsuit for violations of federal clean water law and for infringement on the Tribe’s Treaty rights.

Chronic wastewater pollution impacts marine ecosystems and treaty rights

“In 2019, tribal canoe families from all over the Salish Sea landing in Suquamish during the annual Tribal Canoe Journey had to paddle through one of the county’s largest untreated sewage spills. This pollution, created an immediate health hazard for the tribal community and disrupted an important cultural event,” Forsman noted.

“The Tribe took legal action when it became clear that the County was failing to protect the water quality in Puget Sound as required by the Clean Water Act, and the pollution was interfering with our Treaty fishing rights,” Forsman said. “We could no longer stand on the sidelines hoping conditions would improve.”

The 2019 event was just the latest in a series of pollution events. In July 2020, the Tribe notified King County that it was responsible for at least 11 significant illegal discharges of untreated sewage from the WPTP into the Tribe’s treaty-protected fishing areas, with individual discharge events ranging from 50,000 gallons to 2.1 million gallons. The Tribe further notified King County officials of the Tribe’s intent to file a lawsuit for ongoing violations of the Clean Water Act and its National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit.

Unlawful discharges of sewage foul the water and habitat for aquatic species, result in closure of beaches where Suquamish tribal members harvest shellfish, prompt recalls of commercially sold shellfish, interfere with tribal member harvest and sale of salmon, and disturb important cultural activities such as the annual Canoe Journey. Fecal coliform bacteria pollution is a persistent threat to human health, and the safe harvest and consumption of fish.

The discharges also foul beaches and waterways enjoyed by non-Native residents of King County, Bainbridge Island, Kitsap County and throughout the Puget Sound.

One of the purposes of the Clean Water Act is to eliminate untreated sewage discharges such as those that have been occurring regularly in Puget Sound and to protect the health of all citizens.

Sewage pollution from King County’s outdated wastewater treatment processes are not new. In 2013, King County entered a consent decree with the State of Washington and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address serious and ongoing sewage discharges from the County’s wastewater treatment facilities and combined sewer outfalls. In spite of the consent decree and a series of enforcement actions against King County, Clean Water Act violations continued, including major releases from WPTP that repeatedly impacted the Tribe’s treaty-reserved fishing rights and cultural activities.

Settlement terms designed to protect Puget Sound’s fragile ecosystems

The County acknowledges in the settlement that sewage spill events from its wastewater collection and treatment system into the Tribe’s treaty-protected fishing area have impacted the Tribe’s right to take fish and tribal cultural events, and that this pollution has the potential to impact the Tribe’s treaty rights in the future. However, the County does not admit to liability for any alleged violations.

The settlement agreement requires the County to upgrade infrastructure to eliminate or reduce further untreated discharges from King County wastewater and sewage facilities into Puget Sound. The agreement also requires compensation to the Suquamish Tribe to cover legal and technical costs associated with the discharges, and to compensate for damages. And, importantly, the settlement requires the County to invest in environmental projects that will make up for the damage to marine habitats caused by the spills.

To address tribal impacts, the County agrees to pay the Suquamish Tribe $2.5 million to compensate for impacts to the Tribe associated with the last five years of discharges and future tribal impacts from any additional spills that might occur through the end of 2024. After January 1, 2025, if any sewage is discharged from WPTP’s emergency bypass, the County will will pay a penalty to the tribal mitigation fund for each spill event.

To reduce or eliminate future untreated sewage spills, particularly at WPTP’s emergency bypass, King County agrees to substantial infrastructure upgrades at WPTP. The upgrades include replacing faulty uninterruptible power supply, addressing voltage sag, and creating redundant capacity to deal with peak flows. A strict and enforceable penalty framework is tied to the infrastructure upgrade deadlines, and if missed, the County is required to pay $40,000 for a missed deadline and $10,000 for each additional month of delay

“This framework holds the County accountable for protecting the water quality in Puget Sound,” said Chairman Forsman.

The County will complete supplemental environmental projects tied to nearshore habitat restoration or other mutually agreed environmental protection projects in the amount of $2.4 million within five years.

“The Tribe is pleased that the County negotiated in good faith to protect our shared waters. This settlement will result in significant steps towards protecting the marine life of Puget Sound,” Forsman said

“The entire Puget Sound community deserves clean water. The shellfish, orca, salmon, crab, geoduck and shrimp all rely on a healthy marine environment, and all of our children – and children’s children – deserve clean water,” said Chairman Forsman.