Tribe Bids Farewell to Mike Lasnier

Retiring Suquamish Police Chief Mike Lasnier made his final radio call on March 21, signing off as Chief of Police for the last time surrounded by Suquamish Police officers and staff, tribal members, and law enforcement leaders from throughout the area.

After some 35 years in Law Enforcement, much of that in Indian Country – including 20 years as Suquamish Chief of Police – Lasnier announced earlier this month that it was time to focus more on family. Lasnier was wrapped in a blanket by Tribal Elder Barbara Lawrence who also gifted him with a traditional necklace.

“It has been my great honor to serve you these past 20 years as your Chief of Police,” said Lasnier in his farewell statement to the Suquamish Community. While is leaving was bittersweet, he said he was confident he was leaving the Suquamish PD in a better place than when he arrived.

“I am also confident that the men and women who remain here are ready to take the department to the next level. I am excited to see what the next steps will be for the Tribe and the Suquamish Police Department.”

Lasnier was also honored by Tribal Council at a retirement celebration March 22 with government staff. Tribal Chairman Leonard Forsman, who honored Lasnier with a blanket wrapping, thanked him for his many years of service to the tribe.

Executive Director Catherine Edwards and Human Services Director Jamie Gooby, as well as many staff and fellow SPD officers, also offered words of praise and thanks to Lasnier.

Closure Emergency Contacts

Tribal offices are closed through Jan. 1. For urgent help during the winter break, tribal members and their families may call:

- Court (360) 900-3008

- Education (360) 633-0643

- Health Benefits (360) 394-8424

- Human Services (

- Probation (360) 517-0444

- Public Health (360) 265-0170

- Tribal Child Welfare (360) 394-7143

- Tribal Housing Maintenance – Rental residents can call or text Marcus Mabe at (360) 900-3167

- Victim services (360) 979-6124

- In an emergency, call 9-1-1

Week 4: What Would You Do Wednesday

Thank you for participating in week 4 of What Would You Do Wednesday? We sincerely appreciate your participation and look forward to announcing the winner of the raffle on October 19th, following The Great Washington ShakeOut Earthquake Drill

Boarding School Survivor Peg Deam shares her story

Healing requires restoration of culture, language – and land

When Suquamish Elder Peg Deam was approaching junior high school age, she was sent off to the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in Newkirk, Oklahoma.

“Nothing prepares you for this experience,” she said. “You have no family. You’re just floating out there, trying to survive and get through each day.”

Peg’s life was regimented. Indian languages were forbidden. The food was poor quality. Any sign of Native culture or ceremony was forbidden.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), the school was modeled after the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania, which used “rigorous military discipline and instructions in trades and manual and domestic labor.”

“I thought, this must be what a juvenile delinquency center is like,” said Peg. “Everyone was treated badly.”

Peg’s experience at Chilocco was much like many other Indian children who spent months or years in similar schools, supported by the U.S. government and often run by a church denomination. According to a new report by NABS, there were 523 such schools operating between 1801 and the present.

Children at many of the schools were treated poorly. Like at Chilocco, they were prohibited from speaking their language, and many were physically or sexually abused. Many children attended these schools against their parent’s wishes, brought there when parents were coerced or when children were simply kidnapped.

Many never returned. According to a recent report by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, marked and unmarked burial sites have been identified at 53 federal Indian schools, and many more are expected to be revealed as further research is conducted. Nineteen schools accounted for over 500 deaths of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian child deaths, according to the report.

Many Suquamish Tribal members attended the Tulalip Boarding School. (Photo courtesy of the Suquamish Museum.)

Peg recalled some of what she witnessed at Chilocco. Diné children, many of whom did not speak English, were punished for failing to immediately follow orders they did not understand, she said.

Some of the Sioux boys would pretend to be drunk, knowing they would be handcuffed to the cots in a room together, she said. While there, they were able to secretly speak their language and teach each other traditional songs.

One girl, having learned that her grandfather had died, wanted desperately to conduct the ceremonies necessary when a loved one passes. Her roommates, and girls throughout the dorm, came up with a plan to make that possible. They staged a fist fight on the other side of the building, distracting the matrons long enough to give the girl time to do the necessary rituals for her grandfather.

“We were so proud of each other and especially proud of her,” Peg said. “In an overwhelming situation, she carried on with her culture. I will never forget that.”

Boarding schools and land grabs

It’s long been known in Indian Country that the boarding school policies of the US government were cruel, destructive of Indian ways of life and of families, traumatizing, and did lasting damage to the language and ancestral knowledge of many diverse Native cultures of North America.

The Department of Interior report also demonstrates that the boarding school policy was aimed at taking the land of Indian people so it would be available for white settlers to farm and extract resources.

“Beginning with President Washington, the stated policy of the Federal Government was to replace the Indian’s culture with our own. This was considered ‘advisable’ as the cheapest and safest way of subduing the Indians, of providing a safe habitat for the country’s white inhabitants, of helping the whites acquire desirable land, and of changing the Indian’s economy so that he would be content with less land. Education was a weapon by which these goals were to be accomplished.”

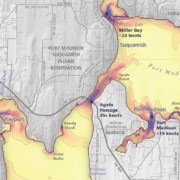

The history of land grabs on the Port Madison Indian Reservation shows how the taking of land coincided with the forcible removal of Suquamish children from their families.

According to Suquamish Chairman Leonard Forsman:

- In 1886: the approximately 8,000-acre reservation was divided into 51 allotments assigned to family “heads.”

Beginning in 1900: Suquamish children were forced to attend Tulalip Boarding School. - In 1904: The U.S. military seized the Old Man House village site where Suquamish people had built their homes, school, church, after the military ordered the burning of Old Man House, former home of Chief Seattle and Chief Kitsap in 1870. The military seized approximately 70 acres of Suquamish waterfront, all in the name of building fortifications to protect the Bremerton shipyard. The fortifications were never built. Instead, the waterfront land was sold to developers who subdivided it for vacation homes for white people. (The deed to those homes prohibited their sale to anyone who was not Caucasian.)

- Circa 1905: Federal government passed law allowing tribal allotments to be sold at auction on behalf of the allottee (resulting in checkerboard reservation)

The timing of these events was not a coincidence, according to Forsman. “Healing begins with a reckoning of what took place, and that means full disclosure, acknowledgment and reparations through land restoration,” Forsman said. As a result of action by Suquamish Tribal Government, more than half of the Port Madison Indian Reservation is now owned by the tribe or by tribal members. The tribe is also supporting the establishment of a national Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding Schools.

Restoring culture and art

For Peg Deam, a main focus has been on restoring Suquamish culture and art.

Deam refused to return to Chilocco after her first year there, instead attending the Institute of American Indian Art (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There, the mostly Native American teachers taught students to embrace their cultural heritage and to learn all they could about their ancestral practices, adding their own creativity to bring their art, writing, theater, and crafts into the present. IAIA, in other words, was the opposite of the Indian boarding schools; instead of punishing children for practicing their culture, cultural practices were taught and encouraged.

Deam is just one of many who resisted boarding school efforts at assimilation, instead embracing her culture. And today, Suquamish is among the communities remembering the hardships of boarding schools; Orange T-Shirt Day will be remembered with a Coastal Jam at the Old Tribal Center on Sept. 29, 2023.

By Sarah van Gelder